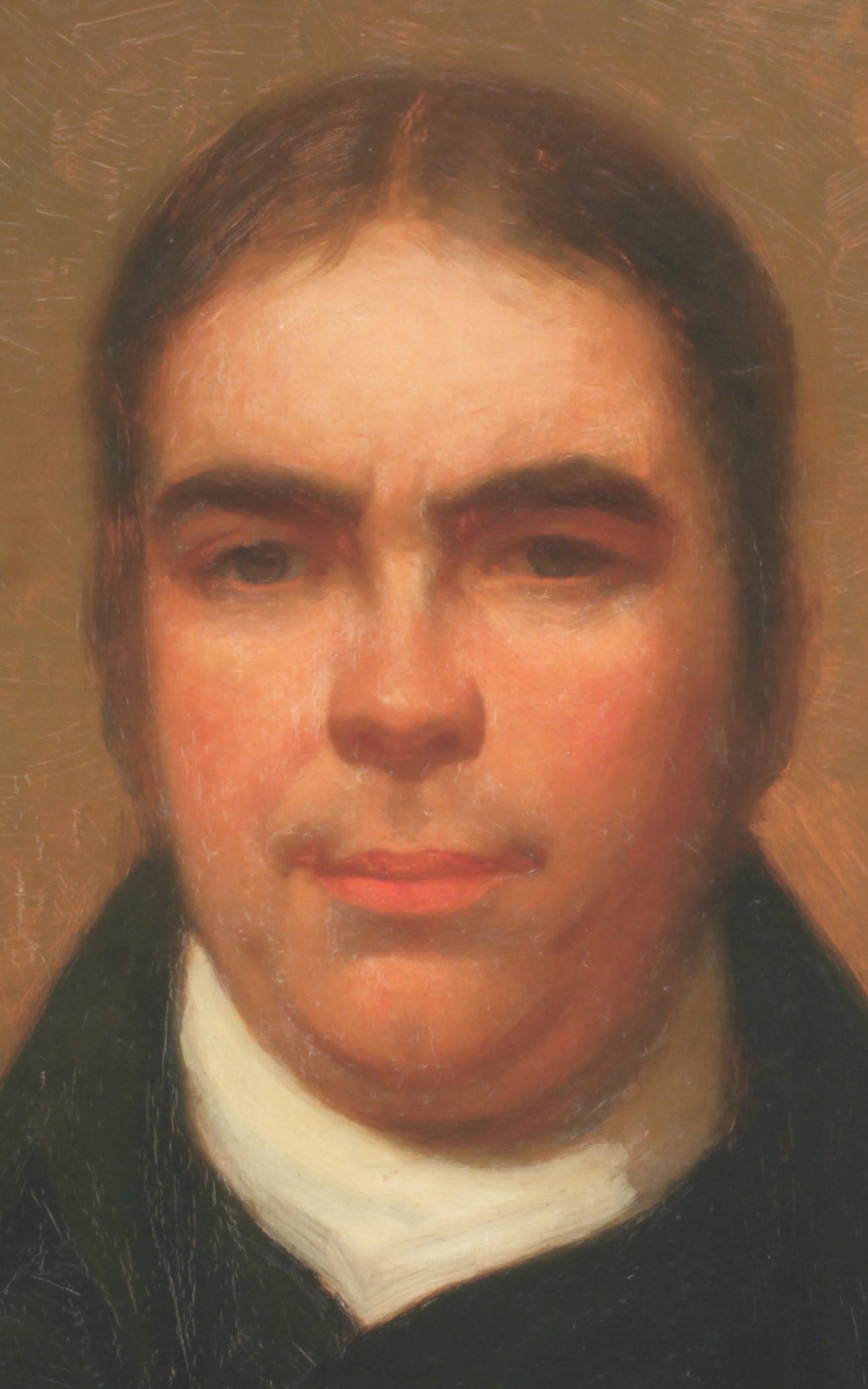

Andrew Fuller, a loving father

Two years after the death of his first wife Sarah in 1792, Andrew Fuller (1754–1815) married Ann Coles (1763–1825), a pastor’s daughter. When Fuller’s mother, Philippa, heard of her son’s impending second marriage, she told him that she wished his “poor children well.” “Have you any reason to fear the contrary?” her son asked her. Philippa Fuller admitted she didn’t, but she reckoned that she herself would “not have made a good step-mother.” Fuller, ever the plain speaker, replied to his mother, “And so from thence you judge that others will be the same. For my part I am persuaded now that I should be a kind father to any family put under my care.”[1] Though rarely touched upon in Fuller studies, Andrew Fuller was indeed “a kind father,” as is well seen in his relationship to his son Robert (1782–1809), who was named after either Fuller’s own father or one of his brothers.

In May of 1796, when Robert was around the age of fourteen, Fuller secured for his teenage son a trial position in the warehouse of William Burls (1763–1837), a successful London merchant and a deacon at Carter Lane Baptist Church in the capital. The situation in Burls’ warehouse, though, did not work out and by 1797 Robert was back in Kettering. The father detected in his son a growing instability, which gave growing urgency to his prayer that his son “might be renewed in his spirit, and be the Lord’s.” An apprenticeship was found for him in Kettering, but Robert was ever restless and in 1798 joined the army. When it was discovered in the army that he was an apprentice he was given a discharge. Again, his father found a position for him, but this too did not work out.

In 1799 Robert joined the Marines. By May of the following year, however, he found he had little liking for this either, and asked his father to see if he could get him discharged. Another discharge was procured and yet another job found for him. But Robert had acquired a habit of roving and had left this position within a month. His father was devastated. “O may the Lord bring me out of this horrible pit,” he wrote in his diary when this occurred, “and put a new song in my mouth.”

Realizing that Robert’s character was such that he would likely not settle down to a trade or business, Fuller was able to get him a position on a merchant ship. But before he could go to sea, he was apprehended by a press-gang of the Royal Navy and impressed as a sailor on a man-of-war. Shortly afterwards, in June of 1801, a report came to the Fuller household that Robert had been found guilty of a misdemeanour and sentenced to three hundred lashes from which punishment he had died! The report turned out to be false, but while it was believed, Fuller felt himself under what he called “a kind of morbid heart-sickness.” Three years later, though, Robert did actually go through such a horrible punishment. He had tried to desert in Ireland, had been apprehended, and sentenced to three hundred and fifty lashes!

When Fuller learned of his son’s experience on July 5, 1804, he wrote to a close friend, John Ryland, Jr. (1753–1825): “I do not expect his recovery; or, if he should live, that he will ever be able to provide for himself. Yet, if this were but the means of bringing him to God, I should rejoice.” Yet, Robert did live. But the lashing destroyed his health and he was subsequently discharged from the navy a few months later.

Fuller and his son were reconciled in London. Robert was placed in the care of an eminent physician who had once lived in Kettering, but now had his practice in the capital. Slowly Robert was nursed back to health, and yet another job found for him. But once again, his old restlessness kicked in and in April of 1805 he disappeared, and for a while his family had no idea where he had gone. Fuller suspected that he had re-joined the army or the navy. He was right. Robert had enlisted among the Marines once more, and putting to sea, he was never again seen by his family.

Yet, his father did eventually hear from him. In December of 1808, after returning from a trip to Brazil and just before a voyage to Lisbon, he wrote to his father in genuine contrition, acknowledging his guilt and foolishness, and longing to hear once again the gospel message of divine forgiveness. His father accordingly wrote him a letter, of which the following marvelous extract is extant:

You may be assured that I cherish no animosity against you. On the contrary, I do from my heart freely forgive you. But that which I long to see in you is repentance towards God and faith towards our Lord Jesus Christ, without which there is no forgiveness from above.

… My dear son, I am now fifty-five years old, and may soon expect to go the way of all the earth; but before I die, let me teach you the good and the right way. Hear the instructions of a father. You have had a large portion of God’s preserving goodness, or you had ere now perished in your sins. Think of this, and give thanks to the Father of mercies who has hitherto preserved you. Think, too, how you have requited Him, and be ashamed for all that you have done. Nevertheless, do not despair. Far as you have gone, and low as you are sunk in sin, yet if from hence you return to God by Jesus Christ, you will find mercy. Jesus Christ came into the world to save sinners, even the chief of sinners.

Less than four months later, in March of 1809, Robert was dead. He died off the coast of Lisbon after a lengthy illness. On the basis of a report by the captain of the ship that Robert was on and from some letters Robert had written to Fuller, the father hoped his son had, before the end came, experienced genuine repentance towards God and faith in the Lord Jesus.

The Sunday after he had received word of his son’s demise, Fuller was preaching on Romans 10:8–9. He pressed upon his hearers the fact that the doctrine of free justification by faith through the death of Christ is for all kinds of sinners. God does not ask how long, how often or even how greatly we have sinned. If we confess our sins, he is faithful and just to forgive us our sins. This great truth, moreover, is suited sinners who find themselves “far from home, and have no friend, in their dying moments, to speak a word of comfort.” But God is near. For instance, Jonah, Fuller declared, “was compassed about by the floods” and “when the billows and waves passed over him, he prayed to the Lord, and the Lord heard him.” At this point, though, Fuller could go no further. Thinking of his son, dying far away at sea and possibly without Christ, Fuller could not hold back the tears. And it was with great difficulty that he finished the sermon that day by urging his hearers to flee to Christ while there was still time.

Thankfully the story does not end there and we know more than Fuller knew during his earthly life. In 1845 Andrew Gunton Fuller, one of Fuller’s sons by his second marriage, was visiting Falkirk in Scotland, where he met a Mr. Waldy, a deacon in the Baptist church there. It appears that Waldy had served with Robert Fuller during his last voyage. He told Andrew Gunton Fuller that he and Robert had “opened our minds much to each other.” In Waldy’s words, Robert “was a very pleasing, nice youth, and became a true Christian man.” And so Andrew Fuller’s many prayers for his wayward son were indeed answered and Psalm 126:5 powerfully illustrated: “They that sow in tears shall reap in joy.”

This article first appeared on TGC—Canadian Edition on July 28, 2019 as Michael A.G. Haykin, “ ‘A kind father’: Biblical fatherhood illustrated in the life of Andrew Fuller.” Used by permision.

[1] Andrew Gunton Fuller, Andrew Fuller (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1882), 74–75.