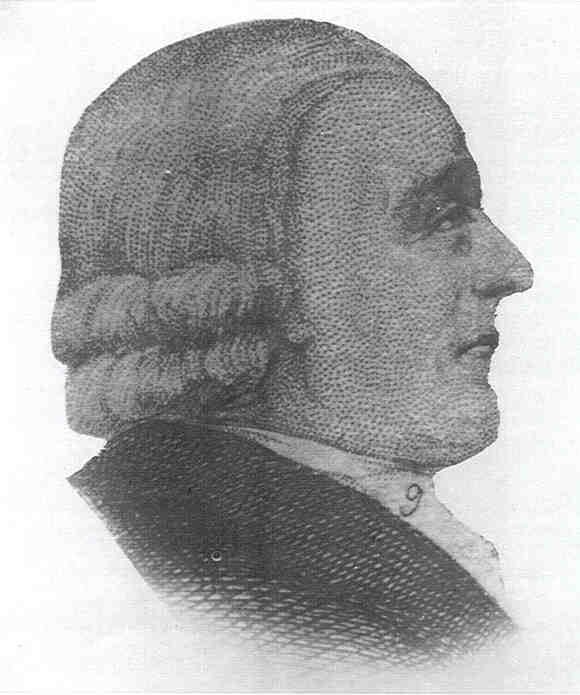

There are two pictures of John Sutcliff (1752-1814) of Olney, whose life I wrote in the early 1990s. The one above is from a composite from the mid-19th century of about 100 Baptist ministers with the redoubtable John Gill at the centre.

My book on his life—which in many was a like a second thesis, I now realize—contains the second pic, which is a silhouette. See below.

Sutcliff and his friends—Andrew Fuller, the younger John Ryland, William Carey, and Samuel Pearce, in particular—were vital for my self-understanding in my early years as a Christian historian.

I had been saved in a Baptist church in Hamilton, ON, where the minister for many years had been C.J. Loney, one of the right-hand lieutenants of the famous fighting Fundamentalist T.T. Shields of Toronto, whose shadow dominated evangelical Baptist life in Canada throughout the 20th century (even long after his death in 1955).

And to be utterly honest I had very little liking for Shields’ Fundamentalism. Yes, it had saved the Gospel for Baptist churches in Ontario (for that I was immensely grateful), but it was marked by an obstreperous, fissiparous, hubristic spirit that spawned a narrow-minded legacy—something I found deeply distasteful.

Arnold Dallimore, the remarkable Canadian Baptist historian, well captured Shields at his worst when he said, that “with all his matchless gifts,” he was little “better than a spoiled child” for whom “a good spanking” was in order! Frank and brutal, but true.

As I discovered the background of the church in which had been converted, I longed for a different heritage. For a number of years in the late 1970s and early 1980s, I thought about becoming an Anglican. But I could not reconcile myself to infant baptism nor to the idea of episcopacy.

But then I found a Baptist heritage that was both firmly evangelical and yet deeply attractive in 19th-century Ontario Baptists like William Fraser, R.A. Fyfe, D.A. McGregor (all Scottish-Canadian Baptists) and even more so in the circle of 18th-century friends around John Sutcliff.

Over the past nine years, my angst about being an evangelical Baptist has come back with a vengeance. I have found the evangelical world in North America increasingly a place of anger and rage and bitter denunciations—the very picture of a new fighting Fundamentalism. Oh, certain elements of theology might be different (e.g. those of eschatology or political theology), but the ethos I all too readily recognize: fissiparous and unsympathetic, and all too quick to condemn, and deeply unattractive.

I have thought about junking my identity as an evangelical and simply describing myself as a Particular Baptist (which is the tradition with which I most readily identify) or a Reformed Catholic (to hearken back to a term once used of himself by William Perkins). If my being a Baptist was what I questioned for a while in the 1970s and early 1980s, now it is my being an evangelical.

Again, what has saved me is both Holy Scripture—I still believe that the evangelical tradition best captures key features of the New Testament ecclesial world—and the circle of friends associated with John Sutcliff. Those men in that now far-off world of early modern Britain: what men they were!

They were solidly confessional and Calvinistic, shaped by the Particular Baptist tradition that stemmed from the halcyon days of 1640s and 1650s and the writings of America’s Augustine, Jonathan Edwards. And yet they were men of deep compassion and benignity, men of rich sympathy and yes, empathy (think here of Abraham Booth’s remarkable sermon on the slave-trade), for whom Christian friendship was of first importance. As Sutcliff once said, “Christian friendship is the sweetest of all connections. It is the very life and soul of every other.”

With such an evangelical band of Baptist brothers I have over a lifetime of teaching and writing identified—and now is not the time to let go! And it is yet another way in which I identify with that saying of Samuel Davies that I recently commented upon, “The venerable dead are waiting in my library to entertain me and relieve me from the nonsense of surviving mortals.”

Professor Haykin, who would say was the most “Evangelical” among the Fathers? Augustine? Hiliary of Potiers? Chrysostom?

Amen! In my opinion, we mustn’t let a few bad apples (well, maybe more like an ever-growing heap) spoil such terms as evangelical. Thank the Lord for the great cloud of witnesses who have gone before us with whom we can find camaraderie.