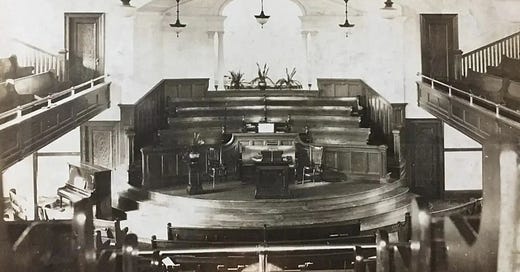

Above: the sanctuary of Stanley Avenue Baptist Church in Hamilton, ON (now Blessings Christian Church [https://blessingshamilton.ca/] circa the 1920s.

“A dismal region of moral darkness and the shadow of death” where most families had “no books, not even a Bible,” and thus were “grossly ignorant” was the way that the American Calvinistic Baptist missionary Asahel Morse (1771–1838) described Upper Canadian society in the first decade of the nineteenth century.[1] Morse’s perspective is undoubtedly shaped by the fact that he was the product of a long-line of preachers—his father, for example, had been converted under the preaching of George Whitefield (1714-1770)—and that he could never remember a time when he was unable to read.[2]

When Morse wrote these words, Baptist life in Ontario was little more than embryonic.[3] By that time fourteen churches had been founded, nearly all of them planted along the shores of either Lake Ontario or Lake Erie.[4] These churches had some 400 members and were linked together in two fledgling associations.[5] The Thurlow Association, which had been formed in 1802, consisted mostly of churches between Coburg and Kingston. The Clinton Conference, formally a part of the powerful Shaftesbury Association of Vermont, New York, and New Hampshire until 1819, was made up of four churches—Charlotteville (Vittoria), which was founded in 1803, Townsend (Boston), organized in 1804, Clinton (Beamsville), and Oxford (later Thames Street Baptist Church, Ingersoll). Each of the Baptist causes in these two associations was the result of extensive missionary efforts on the part of a number of American Calvinistic Baptist Associations.

The Vittoria & Boston Baptists: challenges and commitment

Of all the Baptist churches in Ontario the Vittoria church, organized in 1803, had the oldest continuous existence up until June 2013, when the twenty members of the Church voted to disband.[6] Something of the arduous efforts involved in establishing them can be seen in the following account by John Winterbotham (d.1868) about the founding of the Baptist cause at Vittoria. Winterbotham, a Yorkshireman who had pastored in Haworth, West Yorkshire, a famous centre of revival in the previous century, had immigrated to Ontario in July, 1842.[7] He had subsequently become the pastor of the First Baptist Church in Brantford and the editor of The Christian Messenger, a forerunner of The Canadian Baptist. Winterbotham notes that in the 1790s the area around Vittoria was “almost an unbroken forest, having only a very few human habitations scattered here and there in the thick woods down to the shore of Long Point Bay.” American Baptist missionaries seeking to plant Baptist works in the new country, Winterbotham continues:

…had to traverse the country all the way from Niagara River to Long Point, across swamps, over rivers and creeks, and through trackless woods, thus evincing their love for the souls of dying men. Meetings had been held…in log barns and houses, and when the weather permitted under the shade of lofty trees, whose huge branches screened the humble worshipers from the scorching rays of the sun.[8]

Early Ontario Baptist theology

Theologically, the Association to which the Vittoria Baptist belonged to was Calvinistic in doctrine. The statement of faith of the Clinton church, recorded in the October 17, 1807 minutes of this work, well illustrates these churches’ Reformed position. In the fourth and fifth articles it is unequivocally stated that “all that ever will be saved were chosen in Christ before the world began” and that “all whom God chose in eternity he will call in time by his efficacious grace, and qualify them for, and bring them to his kingdom of glory.”[9] In the American Calvinistic Baptist tradition out of which these Ontario churches sprang there was also a strong commitment to a closed communion polity. The Charlotteville statement of faith specified that “none have a right” to participate in the Lord’s Supper but those “have been duly baptized” as believers and “received into the church.”[10]

A shared ecclesial tradition thus united these early pioneer churches, one that was rooted in Calvinistic soteriology and the practice of closed communion.[11] Such a common doctrinal heritage, though, does not appear to have resulted in significant numerical growth during this early period of Baptist witness in Ontario.

Nineteenth-century Baptist individualism is one key reason for the poor growth of Baptists in colonial Ontario. Especially under the impress of the writings of influential theologians like the Northern Baptist Francis Wayland (1796–1865), Baptists in Ontario, like their cousins in the United States, began to lose touch with “the early connectionalism which had Baptists together in associations” in both the British Isles and colonial America. Instead, the contention began to be made that local churches are independent democracies and that “it was both wrong and dangerous to speak of the “interdependence” of churches.”[12] As one Baptist later said in 1853 about the negative impact that this rugged individualism had had upon early Baptist life in Ontario:

Had the Baptist of Canada laid aside their mutual jealousies at an earlier day, and concentrated their strength in aggressive movements upon the domains of sin and error, not only would our denominational statistics have reached a higher figure, but what is of infinitely more importance, Christ would have been more honoured by us…[13]

Educating Baptists

Yet another reason that could be mentioned for the struggles of the Baptists to establish themselves in Ontario would be their lack of commitment to theological education. It would not be until 1860, nearly eighty years after Baptist had first come into Ontario that they would have a successful school for training pastors, what was known as the Canadian Literary Institute in Woodstock.

This school became a reality in the summer of 1860 when it formally opened with seventy-nine students and five teachers. In a report that was drawn up with regard to the 1856 Baptist gathering that had led directly to the building of this school, the Baptist leadership behind the school were hopeful that they had “entered upon a new and more prosperous era in the history of our denomination in Canada.”[14] They were right. Ontario Baptists had indeed entered upon a new, and far more fruitful, phase of their history. And much of that fruitfulness was linked to the school at Woodstock. It is not fortuitous, therefore, that the motto of the school—given to it by R.A. Fyfe (1816–1878)—was Sit Lux, “Let there be light.”[15]

Not surprisingly, Fyfe was asked to head up the school as its first principal. He resigned from his Bond Street pulpit in Toronto in mid-March 1860 and by mid-June was in Woodstock. He had come from a demanding and busy pastorate and he had no time for rest before assuming the challenge of his new position. As he wrote to an old friend, Daniel McPhail (1811–1874), who has been remembered as “the Elijah of the Ottawa Valley” because of the power of his preaching and prayers:

The confidence which my brethren in the ministry have, almost to a man, expressed in me as Principal, has affected me in a manner beyond my power to describe. While it encourages me, it makes me tremble. Who is sufficient to mould and train our rising ministry? I hope you and the ministry generally, as well as the churches generally, will remember me at the Throne of Grace. Will you not have some set time, some monthly season, of prayer for God’s blessing on the Institute?… I should be glad if I could get a few days or weeks rest, before entering upon my new duties, for I feel weary and my toils and anxieties for the past year have been very great. But I fear I shall get no rest.[16]

Fyfe’s fear was well-founded. Though the school grew to a peak of 253 students by 1874 and was enormously influential in giving shape and cohesion to the Baptist cause in Ontario—some of its key leaders like E.W. Dadson (1845–1900) and its first overseas missionaries, John McLaurin (d.1912) and Americus Vespucius Timpany (1840–1885), were students under Fyfe[17]—it took a heavy toll on the Principal. Every school year between 1861 and his death in 1878 from diabetic complications Fyfe regularly taught six hours a day, five days a week. On Sundays he never declined an opportunity to preach and conduct Sunday School classes. And in the summers he would travel the length of the province raising funds for the school. In the entire seventeen years that he was principal he only took two vacations and all but worked himself to death.

When Fyfe died in 1878, a number of Ontario Baptists raised the idea of re-locating the theological department of the Canadian Literary Institute to Toronto. They were anxious to have a distinctive and influential Baptist voice in the political and economic centre of the province. Fyfe had long argued for a better-educated Baptist ministry to raise denominational respectability.[18] It is not surprising that some of his fellow Baptists, a goodly number of them upwardly mobile businessmen, also wanted to couple this with a growing influence in the public sector of society. The key individual who argued for such a move to Toronto was William McMaster (1811–1887), an Irish immigrant from Ulster, who arrived in Toronto in 1833 and soon became a partner in, and then sole proprietor of, a dry goods firm. Concentrating his energies on wholesaling, he became one of the wealthiest men in Toronto and by the 1850s had entered into banking. He subsequently helped found the Canadian Bank of Commerce in 1867, and as its first president built it into the leading bank in Ontario. A member of Jarvis Street Baptist Church—the Bond Street church had relocated to the north-east corner of Jarvis and Gerrard Streets in 1875—he provided the more than $100,000 to make possible the erection of the substantial Gothic church building that would become the premier Baptist Church in Canada in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. At a lengthy meeting of the denominational leadership in First Baptist Church, Guelph, on July 17, 1879, McMaster and his friends carried the day and it was decided to move the theology department of the Canadian Literary Institute from Woodstock to Toronto. McMaster donated a site on Bloor Street for what was to be called the Toronto Baptist College.

The McMaster controversies

Toronto Baptist College wrestled with theological issues almost from the beginning of its existence. In 1883, for example, William Newton Clarke (1841–1912), a key liberal theologian of the late nineteenth century, was appointed professor of New Testament. In his four years at the school, his liberal views of the Scriptures do not appear to have been challenged. He spurned what he called “the impossible doctrine of divine inspiration” and noted in his diary for January 1, 1887: “Believing the Bible was once held practically as more vital to religion than loving and trusting Christ; it was thought a part of religion to believe that Ruth married Boaz.”[19] Then, in the first decade of the twentieth century, the Old Testament Professor I.G. Matthews (1871–1959) aired disturbing views about the authorship of various Old Testament books. The controversy that erupted led to his eventual departure for the United States in 1919.

The most significant of controversies about McMaster, though, came between 1925 and 1927, when Laurance Henry Marshall (1882-1953) was appointed as the Professor of Practical Theology in 1925.[20] Marshall was an Englishman with an extremely winsome personality and a powerful pulpit presence. The church that he had pastored in England before coming to Canada—Queen’s Road Baptist Church, Coventry, the largest Baptist work at the time in the Midlands—long remembered him as a pulpit orator, whose style was reminiscent of some of the great Victorian preachers. In fact, when Frederick Griffin, an experienced reporter with The Toronto Star in the 1920s, heard Marshall speak at the tumultuous national convention of the Canadian Baptists in 1926, he felt there was only one equal to Marshall’s “flaming, magnificent speech” and that was a talk given many years before by the Canadian Prime Minister, Wilfrid Laurier.

But there seems no doubt that Marshall had definitely imbibed significant doses of liberal thinking. In an article written a few years after the controversy, Marshall declared his support for the theory of evolution, his rejection of the infallibility of God’s Word, and his intense dislike of viewing the death of the Lord Jesus as being vicarious punishment for the sins of his people.[21] Marshall seems to have regarded the message of Scripture as inspired, but not the text itself. And with regard to the doctrine of the atonement, Marshall saw the crucifixion of Christ as the supreme example of divine love, but not a propitiation for the sins of sinners. There is also evidence that Marshall was not entirely comfortable with affirming the bodily resurrection of Christ. One of the pastors who sided with Marshall during the twenties later admitted that Marshall “was not in harmony with the beliefs of many of our people.” At the time, however, McMaster’s administration, especially Jones H. Farmer (1859–1928), the Dean of Theology, and the Chancellor, Howard Primrose Whidden (1870–1952), were adamant that Marshall was orthodox.[22] In some ways, Farmer’s defence of Marshall is odd, for Farmer was a man who could rightly declare in a Baptist church in Lindsay in November, 1927, that he had steadily opposed “any type of Modernism that would take the crown from the brow of Jesus Christ.”[23]

The leading critic of Marshall and the leadership of McMaster University was Thomas Todhunter Shields (1873–1955), pastor of Toronto’s Jarvis Street Baptist Church for most of his adult life, and, as the liberal Protestant periodical The Christian Century put it in 1929, “unquestionably the dominant personality” among North American conservative Christian leaders of that era.[24] As a person Shields was strikingly different from the winsome Marshall, for to some people he appeared to be abrasive and often domineering. One contemporary, for example, a certain F.F. MacNab, went so far as to call him the “Pope of Jarvis Street.”[25]

For two years, between the Ontario and Quebec Baptist Conventions of 1925 and 1927, all-out war—by means of the spoken word, the printed page, and various rallies throughout Ontario—raged relentlessly between Shields and his allies and those siding with Marshall. But this Baptist controversy of the 1920s was not ultimately about personalities, but faithfulness to God’s Word. As Leslie K. Tarr, who has written the only major published study of Shields, once asked: “Even if Shields was abrasive and provocative, does that in itself invalidate his accusations?”[26] In the final analysis, it must be recognized that, in spite of Shields’ difficult personality, it was his fidelity to biblical truth that did so much to prevent the dilution of biblical truth among Ontario Baptists.[27]

Finally, things came to a head at the 1927 annual Convention. Marshall defended his views and asked the Ontario and Quebec Baptist church delegates at convention in 1927:

Are we as Baptists to stand for ignorance and obscurantism and intolerance, or are we to get into line with all the truly great men whose names are written upon our Baptist roll of fame, (and the greatest of them all in my humble opinion is Wm. Carey the great pioneer of modern missionary enterprise) and stand for sound scholarship, for the love of truth, for tolerance, for reasonable liberty, with the McMaster motto as our watchword: “In Christ all things consist.”[28]

Marshall’s appeal to standing in the line of “all the truly great men” of the Baptist past—in particular, William Carey, one of the leading pioneers of the modern missionary movement—seems to indicate that Marshall was convinced that his brand of non-confessional Baptist theology was the norm in Baptist history. There have always been a small minority of Baptists that have had a distrust of creeds and confessions, but Marshall was wrong to think this was the norm, or that William Carey could be found among them. But, as it turned out, Marshall’s position was vindicated by the 1926 and 1927 annual Conventions, and Jarvis Street Baptist Church, where Shields was the pastor, was subsequently expelled from the Convention along with a dozen other recalcitrant churches.

The Union and the Fellowship

Within a year of these momentous events, 65 other churches had left the Convention in sympathy with Jarvis Street. About a seventh of the churches of the Convention had thus either been expelled or left. These churches soon committed themselves to the formation of what eventually became known as the Union of Regular Baptist Churches of Ontario and Quebec. The founding convention took place at Stanley Avenue Baptist on November 27–30, 1928, with 77 churches represented. The membership of these churches was around 8,500.[29] In the Stanley Avenue Minute Books the event was noted as “an historic occasion…a splendid gathering: the services being bright, happy and inspirational.”[30]

There were great hopes of steady growth for the Union but it was not to be. By 1931 the Union had nearly 90 churches.[31] But controversy over the relationship between the Union and two of its ministries—The Fundamentalist Baptist Young People’s Association and The Women’s Missionary Society of Regular Baptists of Canada—between 1931 and 1933 resulted in the loss of a number of congregations so that by 1933 there were only 60 churches or so in the Union. Essentially Shields was insistent that both of these organizations needed to be firmly under the authority of the Union churches. At least nine pastors within the Union disagreed and they were expelled from the Union in the summer of 1931.[32]

Two years later, these expelled ministers and their churches joined with other like-minded congregations who had never been part of the Union to form the Fellowship of Independent Baptist Churches of Canada. In the words of Norman W. Pipe (1909–2000), a key figure in this body of the churches, these churches were insistent upon “a minimal amount of organization and business, and a maximum amount of fellowship.” The battles of the 1920s against theological liberalism and then the internecine fighting amongst Fundamentalist Baptists in Ontario between 1931 and 1933 had left the leaders of these congregations with a deep distrust of any organization beyond the level of local church.[33] On the other hand, they also saw themselves as preserving what they regarded as “one of the greatest principles of Baptist polity—the New Testament doctrine of the Sovereignty of the local congregation,” to quote one of their key leaders, John F. Holliday.[34] Between 1933 and 1950 this body of churches grew from 27 congregations to 124.[35] In addition to both of these groups of Baptists, the Union and the Fellowship, there were other unaffiliated Baptist congregations who had left the Convention but refused to join either the Union or the Fellowship.[36]

“Not spend our time wrangling”

Yet another serious battle within the Union took place in 1937. On this occasion, it concerned the Union’s foreign mission work in Liberia. The 1940s saw further controversies within the Union till finally in 1948 and 1949 came the straw that broke the back of the proverbial camel. This final controversy centred on T.T. Shields’ removal of W. Gordon Brown (1904–1979) in December of 1948 from his position as the Dean of Toronto Baptist Seminary. Brown had taken his B.A. at McMaster and subsequently played a key role in the McMaster Controversy. He later earned an M.A. at the University of Toronto. After a term of study at Southern Baptist Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky, in 1930, he began teaching full-time at Toronto Baptist Seminary in the fall of 1931. The influence of Shields upon Brown, by the latter’s own admission, was enormous.[37] Brown had served faithfully both as a teacher and Dean at Toronto Baptist Seminary until this division between him and Shields. While personality and temperament undoubtedly played major roles in this conflict between Shields and Brown, a difference of opinion about the nature of the seminary was also at the heart of the split. Shields was averse to allowing students from the Fellowship into Toronto Baptist Seminary, while Brown “deliberately cultivated” links with the Fellowship and her ministers, and wanted their students in the school.[38]

After Shields had dismissed Brown, he planned to issue a statement defending his actions. Two graduates of Toronto Baptist Seminary, Hal MacBain (1916–2016), pastor of Temple Baptist Church in Sarnia,[39] and Jack Watt (1913–1991), then pastoring Campbell Avenue Baptist Church in Windsor, went to see Shields, hoping to dissuade him from issuing such a statement as it would only inflame the controversy and foment division with the Union. They also hoped that Shields would agree to seek reconciliation with Brown. MacBain actually thought they had made some headway in convincing Shields not to go public, but he was wrong.[40] Jack Scott (1914–1981), the pastor of Forward Baptist Church in Toronto, also pleaded with Shields by means of a letter to avoid further rupture in Baptist ranks. In Scott’s words: “There should be a spirit among the churches of evangelical Baptists that we should go out and preach the gospel, build churches, get souls saved, get involved in missions and not spend our time wrangling.” But Scott’s plea, like those of MacBain and Watt, fell on deaf ears and the split came.

A majority of the teachers and around 50 of the 75 students at Toronto Baptist Seminary sided with Brown and formed, in January 1949, what would become Central Baptist Seminary.[41] Brown was the new school’s first dean, a position he held until 1973, and the President was Jack Scott. Shields’ authoritative influence in the Union had clearly come to an end. The Jarvis Street pastor pulled his church out of the Union and with a small group of churches formed what came to be known as the Association of Regular Baptist Churches, which disbanded around 2003. Many of the Union pastors had sat under Shields’ teaching at Toronto Baptist Seminary and never forgot what they owed Shields: in the words of Hal MacBain, “there can be no doubt that Dr. Shields was an outstanding preacher” and “taught us much on how to do things in the ministry.” But they also learnt, as MacBain put it many years later, that “there were better and more peaceful ways of accomplishing God’s purposes.”[42]

Forming the Fellowship of Evangelical Baptist Churches (FEBC)

After the break with Shields, the Union churches considered themselves now free to pursue closer ties with the Fellowship. Hal MacBain was elected president of the Union of Regular Baptist Churches and in November of 1951 made public a prayer that he had been praying for a while: “May God give us all a vision in our individual churches of spreading the glorious truths of the Gospel that have made us rich in Christ Jesus, to neighbouring towns and cities, to the dark reaches of the exploited province of Quebec, yea even unto the uttermost parts of the earth.”[43] Now, it was clear to MacBain and other pastors within the Union that part of the answer to this prayer lay first in building bridges to the Fellowship churches, many of which were also desirous for closer ties of fellowship.[44]

Thus, in the fall of 1952, when the annual convention of the Union was held at Temple Baptist, Norman Pipe and Donald Loveday, the Moderator and Vice-Moderator respectively of the Fellowship, were invited to attend the convention as the possibility of a merger between the Union and Fellowship was discussed. There was even a Baptist pastor from British Columbia present, E.V. Apps, whose “message to us was an invitation to co-operation.”[45] Some within the Convention of Regular Baptists of British Columbia, which had been formed in the summer of 1927 also in response to liberal theology within the Baptist Union of Western Canada,[46] were seeking to build ties with other Baptists in the 1950s. For example, between 1953 and 1955 five Regular Baptist Churches, from British Columbia and the Prairies, would join the Southern Baptists as they moved into Canada.

Along with many at the convention, MacBain “felt the common bond of our heritage and faith and practice [with the Fellowship churches] drawing us together to a closer brotherhood, and also to a more definite integration of our work.” MacBain rightly emphasized that the great need of their day, with the growth and size of Canada as a nation, was “for a firm and solid front of Evangelical Baptist effort,” and he was deeply grateful that the delegates to the convention approved in principle “the desirability of the coming together of the Union and the Fellowship.”[47]

Of course, there were those within the two bodies of Baptists who had problems with the concept of merger. For example, Ernest Edgar Shields (1877–1952), the younger brother of T.T. Shields, was concerned about the practice of open communion among the Fellowship churches. In the mid-1940s, differences among the Fellowship Baptists with regard to allowing believers who had not been immersed as believers partake of the Lord’s Supper were aired in their official publication, The Fellowship Evangel.[48] Shields thus informed John Armstrong in September of 1950:

For some years I have advocated Union with the other body [i.e. the Fellowship]. But when I learned of the “Open” and “Close” controversy, I came to the conclusion that we should not unite unless and until the matter was settled by them in favour of the “Close” view. Recently I have learned on good authority that two of their main churches and perhaps three, are “open” in practice. As I think at present, I should strenuously oppose union with any other than “Close” churches. Open communion leads logically to open membership. Open membership means that, in cases, unbaptized members may come to outnumber the baptized members. This necessarily will soft-pedal the preaching—and therefore the practice—of immersion.[49]

On the other hand, there were pastors in the Fellowship who feared that merger would endanger the autonomy of their local churches and they felt threatened by any amount of organization beyond the bounds of the local church. It was these pastors who would insist at the time of the merger of the Union and the Fellowship that Central Baptist Seminary should not be owned by the new fellowship of churches, a perspective that would have significant consequences for the future of theological education for this body of churches.[50]

MacBain, though, was assured that Canada needed “a united evangelical Baptist testimony.”[51] MacBain was to play a critical role in the merger of these churches. Arnold Dallimore, pastor of Cottam Baptist Church, noted in May 1951 that the pastors of the Union churches, “continually look” to MacBain “for leadership and expect his wise and steady counsel on all matters of policy.”[52] MacBain’s “calm approach to every question or problem, his analytical mind, and his simple answers or solutions,” in the words of Jack Watt, were just what were needed to help shepherd this union of churches.[53]

Full-fledged union became a reality on October 21, 1953, in what would henceforth be known as the Fellowship of Evangelical Baptist Churches in Canada.[54] In the words of Kenneth Davis, this merger was “a major triumph for evangelical Baptist unity” that brought together 194 Baptist congregations.[55] The statement of faith of the FEBC was solidly evangelical and moderately Calvinistic, and the communion question that had been an issue for E.E. Shields was resolved by the affirmation that the ordinances are “regularly observed in the New Testament in the following order” of baptism first, then the Lord’s Supper.[56] MacBain believed that the use of the adjective “evangelical” in the name for this body of churches was especially significant:

…we are denominating our local churches as churches which believe in propagating the glorious evangel of the grace of God. We are at the same time clearly identifying ourselves with a great host of honoured servants of God of past years. C.H. Spurgeon was an evangelical Baptist; so was William Carey; and so were John Bunyan, Adoniram Judson, and a great host of others so familiar to us all. We cannot help but look forward to the use of this simple and honoured word to describe us as Baptists.[57]

Coda

By 1965, the FEBC had become a nationwide body of churches, having been joined by the Regular Baptists of British Columbia, which had begun in 1927, and Baptist congregations in the Prairie Provinces Convention.[58] By that point in time, there was also one FEBC congregation in the Atlantic provinces, Faith Baptist Church in Sydney, Nova Scotia, and the FEBC truly reached a mari usque ad mare (“from sea to sea”).[59]

In a statement made in 1953, at the time of the merger of the churches of the Union and Fellowship, Hal MacBain, who was elected as the first President of the FEBC, stated that it was the founders’ desire that the FEBC be a “swift moving stream, blessing and refreshing all who may come in contact with it.”[60] A sizeable group of people from across Canada, including this author, thank God that, in his gracious providence, this desire has been realized time and again.

[1] Stuart Ivison and Fred Rosser, The Baptists in Upper and Lower Canada before 1820 (Toronto, ON: University of Toronto Press, 1956), 52–53.

[2] Ivison and Rosser, Baptists in Upper and Lower Canada, 76–77.

[3] For a good account of this period in Ontario Baptist History, see Ivison and Rosser, Baptists in Upper and Lower Canada.

[4] For these churches, see Ivison and Rosser, Baptists in Upper and Lower Canada, 82–120.

[5] G.A. Rawlyk, The Canada Fire: Radical Evangelicalism in British North America, 1775-1812 (Kingston, ON, & Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1994), 122.

[6] Monte Sonnenberg, “Vittoria Baptists vote to disband”, Simcoe Reformer (Tuesday, July 30, 2013) (http://www.simcoereformer.ca/2013/07/30/vittoria-baptists-vote-to-disband; accessed May 27, 2016).

[7] Thomas S. Shenston, A Jubliee Review of the First Baptist Church, Brantford, 1833 to 1884 (Toronto, ON: Bingham & Webber, 1890), 17. For his ministry in Haworth, see Robin Greenwood, “West Lane and Hall Green Baptist Churches in Haworth in West Yorkshire: Their Early History and Doctrinal Distinctives” (Unpublished ms., 2002), 71–77.

[8] “Valedictory Services at Vittoria”, The Christian Messenger, 1, no.35 (May 31, 1855).

[9] Cited William Norman Albert Gillespie, “Ontario’s 19th Century Baptist Tradition: Its Roots and its Development” (Ph.D. thesis, University of Waterloo, 1990), 109.

[10] Cited Gillespie, “Ontario’s 19th Century Baptist Tradition”, 131-132.

[11] For a detailed development of this point, see Gillespie, “Ontario’s 19th Century Baptist Tradition” and idem, “The Recovery of Ontario’s Baptist Tradition” in David T. Priestley, ed., Memory and Hope: Strands of Canadian Baptist History (Waterloo, ON: Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1996), 25–37.

[12] Norman H. Maring, “The Individualism of Francis Wayland” in Winthrop Still Hudson, ed., Baptist Concepts of the Church: A Survey of the Historical and Theological Issues which Have Produced Changes in Church Order (Philadelphia, PA: Judson Press, 1959), 136.

[13] “Regular Baptist Missionary Society,” The Christian Observer, 3, no.11 (November 1853): 168.

[14] “What was done at the Convention?,” The Christian Messenger, 3, no.9 (November 27, 1856): 2, cols. 2–3.

[15] Theo T. Gibson, Robert Alexander Fyfe: His Contemporaries and His Influence (Burlington, ON: Welch Publishing Co., 1988), 343.

[16] Cited J. E. Wells, Life and Labors of Robert Alex. Fyfe, D.D. (Toronto, [1885]), 309.

[17] For an estimation of Fyfe’s impact in this regard, see Gibson, Robert Alexander Fyfe, 274–278.

[18] Daniel C. Goodwin, “ ‘The Footprints of Zion’s King’: Baptist in Canada to 1880” in G. A. Rawlyk, ed., Aspects of the Canadian Evangelical Experience (Montreal, QC/Kingston, ON: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1997), 201.

[19] William Newton Clarke: A Biography (New York, NY: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1916), 53 and 60.

[20] For a memoir of Marshall, see Henry Bonser, “A Memoir of the Author: Laurance Henry Marshall 1882-1953” in L.H. Marshall, Rivals of the Christian Faith (London: Carey Kingsgate Press, 1954), 1–15.

[21] In a book published in the 1940s he went so far as to reject the Pauline authorship of the Pastoral Epistles.

[22] See, for instance, J.H. Farmer, “Professor Marshall”, The McMaster Graduate, 5, no.3 (December 1925): 1–3.

[23] “Meeting of Drs. Farmer and MacNeill and Mr. Duncan at Lindsay—November 2nd, 1927” (Typescript ms., Jarvis Street Baptist Church Archives, Toronto, Ontario).

[24] Cited G.A. Rawlyk, Champions of the Truth: Fundamentalism, Modernism, and the Maritime Baptists (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press for the Centre for Canadian Studies, Mount Allison University, 1990), 76.

[25] “An Unfortunate Necessity”, The McMaster Graduate, 5, no.3 (December 1925), 16.

[26] Leslie K. Tarr, “Another Perspective on T.T. Shields and Fundamentalism” in Jarold K. Zeman, ed., Baptists in Canada: Search for Identity Amidst Diversity (Burlington, ON: G. R. Welch Co., Ltd., 1980), 214.

[27] Tarr, “Another Perspective on T.T. Shields”, 223.

[28] The Faith of Prof. L. H. Marshall (Toronto: [McMaster University], 1927), 23–24.

[29] Leslie K. Tarr, This Dominion His Dominion (Willowdale, ON: The Fellowship of Evangelical Baptist Churches in Canada, 1968), 95.

[30] Michael A.G. Haykin, ed., “Lord God, Our Thanks to Thee We Raise.” The Minute Books of Stanley Avenue Baptist Church, Hamilton, 1889–1929. A Centennial Volume (Hamilton, ON: Stanley Avenue Baptist Church, 1989), 77.

[31] J.H. Watt, The Fellowship Story: Our First 25 Years ([Willowdale, ON]: The Fellowship of Evangelical Baptist Churches in Canada, 1978), 34.

[32] Dozois, “Dr. Thomas Todhunter Shields,” 88–93.

[33] Norman W. Pipe, “Fellowship of Independent Baptist Churches 1931–1953”, The Evangelical Baptist, 14, no.8 (June 1967): 12; “The Story of the Fellowship,” The Fellowship Evangel, 19, no.2 (March, 1952): 7 and 10. For an excellent overview of this body of churches, see Tarr, This Dominion His Dominion, 105–113.

[34] Cited Tarr, This Dominion His Dominion, 106–107.

[35] Tarr, This Dominion His Dominion, 113.

[36] S.L. White, “Fellowship Baptist Young People’s Association”, The Evangelical Baptist, 14, no.6 (April 1967): 8. On Sidney White, a deacon of Central Baptist Church in Brantford, see Watt, The Fellowship Story, 49–50.

[37] See Kenneth E. Hall, “Dr. W. Gordon Brown: A Biography” (Typescript essay, 1965; copies in Heritage College & Seminary Library, Cambridge, ON, and in the possession of the author), 32.

[38] Geoffrey A. Adams, “Alumni Serving In Canada and the United States” in By His Grace To His Glory: 60 Years of Ministry. Toronto Baptist Seminary and Bible College, 1927–1987 (Toronto, ON: Toronto Baptist Seminary and Bible College, 1987), 28; Hall, “Dr. W. Gordon Brown,” 37–38. For an excellent study of the split between Shields and Brown, see Paul R. Wilson, “Torn Asunder: T.T. Shields, W. Gordon Brown and the Schisms at Toronto Baptist Seminary and within the Union of Regular Baptist Churches of Ontario and Quebec, 1948–49” (Unpublished paper, 45 pages, c.2015).

[39] For his life and ministry, see Michael A.G. Haykin with Baiyu A. Song, “To yield my will, my hopes, my goal, my all”: A Portrait of the Life and Ministry of W. Hal MacBain (Guelph, ON: The Fellowship of Evangelical Baptist Churches in Canada, 2016).

[40] Michael A.G. Haykin, “Interview with Dr. W. Hal MacBain” (Five-page manuscript, April 20, 2000; possession of author), 3.

[41] Watt, The Fellowship Story, 42–43.

[42] W. Hal MacBain, “Personal Memories of Dr. T.T. Shields” (Three-page typescript, n.d.; MacBain Personal Archives), [2–3].

[43] W.H. MacBain, “Forward”, The Union Baptist, 2, no.1 (November, 1951): 1.

[44] W.H. MacBain, Nos Racines (Montreal, QC: SEMBEQ, 1984), 5–6.

[45] W.H. MacBain, “To the Work!”, The Union Baptist, 3, no.1 (November, 1952): 1.

[46] For this story, see William Badke, “First the Gospel: FEBBC/Y” in Michael A.G. Haykin and Robert B. Lockey, ed., A Glorious Fellowship of Churches: Celebrating the History of the Fellowship of Evangelical Baptist Churches in Canada, 1953–2003 (Guelph, ON: The Fellowship of Evangelical Baptist Churches in Canada, 2003), 205–216.

[47] MacBain, “To the Work!”, 1–2. See also MacBain, Nos Racines, 12–14 for MacBain’s defense of “The Theology of Interdependence of New Testament Churches.”

[48] See C.M. Keen, “Is Open Communion Scriptural?,” The Fellowship Evangel, 13, no.4 (April 1946): 5–6, 14–15 and T.J. Mitchell, “Is Closed Communion Scriptural! [sic],” The Fellowship Evangel, 13, no.4 (April 1946): 11–12, 14.

[49] E.E. Shields, Letter to J.R. Armstrong, September 11, 1950 (MG 4–1 File 156 Union Correspondence: Shields, E.E. 1950–1951, Box I5, Archives of the Fellowship of Evangelical Baptist Churches in Canada, Guelph, ON), 2.

[50] Davis, “Struggle For a United Evangelical Baptist Fellowship,” 250–251.

[51] MacBain, “To the Work!”, 2.

[52] Arnold Dallimore, Letter to Grace Ann MacBain, May 28, 1951 (MacBain Personal Archives).

[53] Watt, The Fellowship Story, 48–49.

[54] For details, see Watt, The Fellowship Story, 42–50; Davis, “Struggle For a United Evangelical Baptist Fellowship,” 240–243.

[55] Davis, “Struggle For a United Evangelical Baptist Fellowship,” 243.

[56] See “What We Believe,” The Fellowship (http://www.fellowship.ca/qry/page.taf; accessed November 7, 2016).

[57] W.H. MacBain, “What Kind of Baptist Are You?,” The Union Baptist, 3, no.6 (May, 1953): 2.

[58] See Ian C. Bowie, Jack and Alberta Pickford: Builders of a Baptist Legacy (Richmond, BC: The Baptist Foundation of B.C., 1999), 119–132. For the history of these two bodies of churches, see John S.H. Bonham, “Harvesting on the Prairies: FEBCAST/FEBMID” in Haykin and Lockey, ed., A Glorious Fellowship of Churches, 175–204 and William Badke, “First the Gospel: FEBBC/Y” in Haykin and Lockey, Glorious Fellowship of Churches, 205–230.

[59] Robert B. Lockey, “Fishing for Men: Fellowship Atlantic” in Haykin and Lockey, ed., A Glorious Fellowship of Churches, 45–47. The official motto is drawn from Psalm 72:8. Little known is the fact that there is an annulus behind the shield on the Canadian coat of arms bearing the motto of the Order of Canada, Desiderantes meliorem patriam (“desiring a better country”), taken from Hebrews 11:16.

[60] Cited Tarr, This Dominion His Dominion, 133.

Thanks so much for writing this up, and sharing it publicly!